Family Experiences of Vegetative and Minimally Conscious States

Bereavement after severe brain injury

Families of people in vegetative or minimally conscious states often feel they ‘lost’ their relative a long time before the actual death - families of people with advanced dementia sometimes feel the same way. Until the final (‘real’) death they are in limbo: the person is neither fully with them any more, but neither are they physically gone (for more see ‘Grief, mourning and being in limbo’). The person’s death may be feared: death means that all hope for their recovery is lost. Or it may be wished-for as a ‘release’, finally allowing a peaceful end to the body of a person whose ‘spirit’ or ‘soul’ has already left. Either way, losing someone who has been in a vegetative or minimally conscious state for a long time can feel quite different from either a sudden bereavement, or a loss after a long illness in which someone has been conscious until the end.

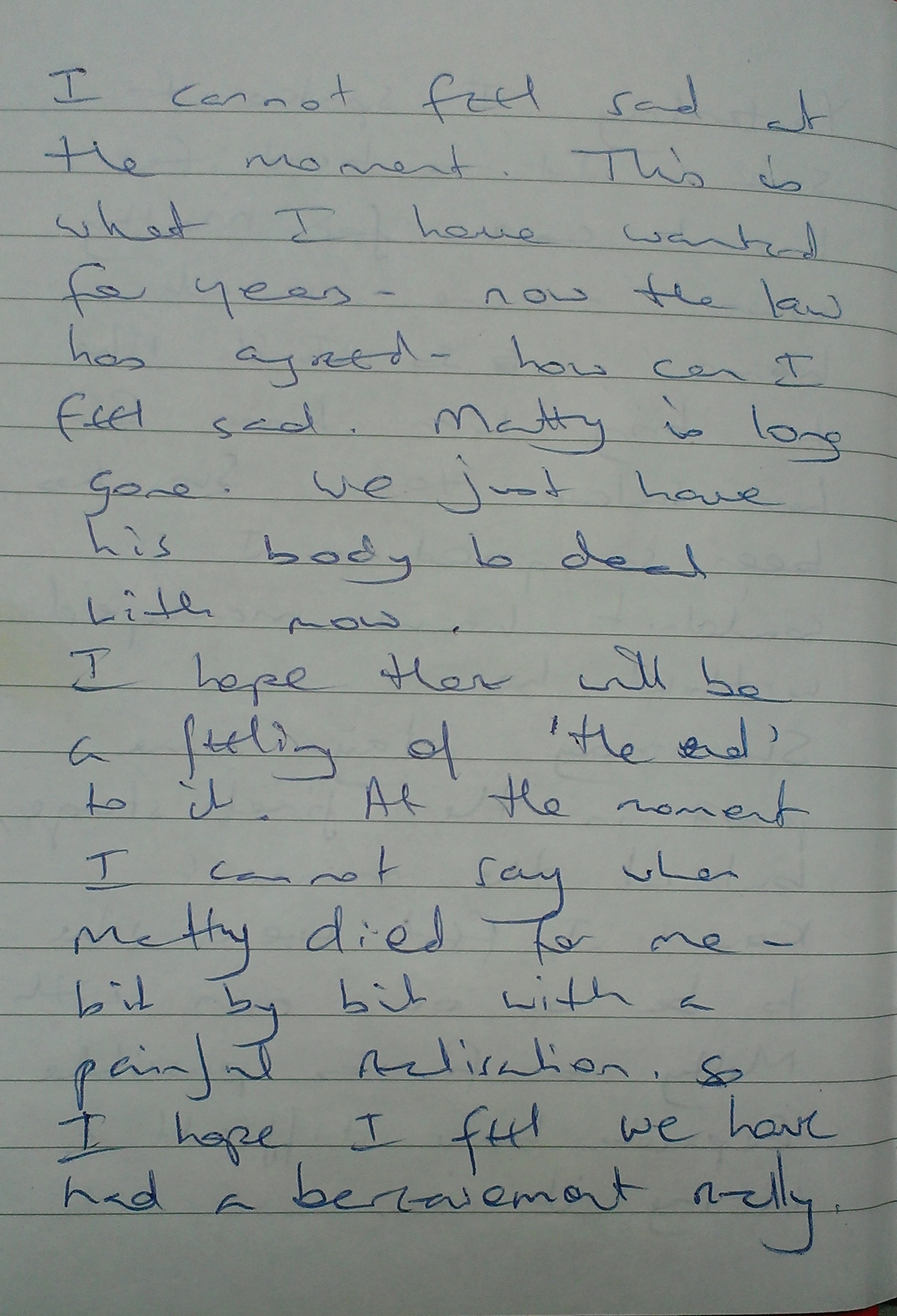

One mother shared her diary entries for the days around her son’s death, eight years after his accident where she wrote about longing for a feeling of “The end” and hoping for a feeling of bereavement.

Some people said they felt a mixture of fear (at finally losing the person) and hope (that the person is released). Some of the bereaved were taken by surprise at how they felt. Daisy thought she had done her grieving years before and was hoping her brother would die. When he did: ‘although it was wonderful that his soul was free and that he was free and we knew that this was the best thing for him, it was a huge loss for us’. She found she was grieving the loss of the minimally conscious man she had looked after for so many years as well the strong, intelligent man he had been before his accident. Memories flooded back - filling her with raw grief. Other people we interviewed felt only relief or calmness – focusing on the fact that the person they loved was now at peace.

The death of his wife, Amber, several months after her injury was a relief for Jim, even though he had never given up hope.

The death of his wife, Amber, several months after her injury was a relief for Jim, even though he had never given up hope.

Yes.

So you must have felt conflicted?

I was. Until I was told she'd passed away. I'll be quite frank. It was a relief. Because I had – I had doubts that even if Amber had survived, if she couldn’t recover – or if she didn’t recover 90% plus, I don’t think she would have been a happy bunny. She was such a vibrant character that I don’t think she would have been happy. And as I say, when I got the phone call to say that she'd passed away, it was a relief.

Right there and then?

Yes.

Despite the fact you hadn’t given up hope?

Yes. I hadn’t given up hope until that second. Although I had reservations as to what quality of life – and it's her life, not my life.

So you would never have – you mentioned earlier the court cases that people have taken to get treatment withdrawn –

Yes.

You wouldn’t have started that yourself, because you hadn’t given up hope?

No.

So you wouldn’t have tried to withdraw treatment?

No.

But a natural death, out of your hands, was a relief?

Yes. It's a very delicate balance. Between okay, did if you like – I mean, don’t get me wrong, I know – we knew what we wanted as a quality of life, and it was safe to say that with Amber laid there like she was, that wasn’t the quality of life she expected. But by the same token, because Amber couldn’t communicate in any shape or form, I never gave up hope because of our past experience of Bernard and Janet. They were two people who were written off. Whether it be right or wrong, I thought they were in a worse state than Amber ever was, because Amber wasn’t on a life support machine. Now that – the interpretation of that might be wrong in that fact that Amber was on permanent oxygen supply and the only method of feeding and administrating medication was through the PEG. But when you've seen or know of two people who were written off for several months and then you see them like they are today, you keep faith.

Yeah, I can see that.

So I never gave – and my friends never gave up hope that Amber would survive. Although we didn’t know to what extent, and whether Amber would have been happy to make the most of her life in that diminished state, who knows?

So the decision was taken out of your hands, she died?

Yes.

And that was the relief?

And it was a relief.

Did you feel guilty about feeling a relief?

No. Because although there were signs of improvement I knew that it would be a very long process for Amber to recover any one of the things she lost to near normality. And there was always this question that Amber was such a vibrant person, would she be happy say living – being alive and only having 75% of her faculties. From the discussions we had, I don’t think she would have been. But by the same token, as we know from these two people which as I say we know in detail, they are enjoying their quality of life. Although they have these disabilities and restrictions and come what have you, but they're enjoying – they're living with it.

David and Olivia did their grieving over the five years before the final death.

David and Olivia did their grieving over the five years before the final death.

So, like I say, I wasn’t – you know, I was sad but I wasn’t unhappy, you know, when, when she passed. I think it was, it was right, it felt – everything felt right. And it was finally over for her, you know, she could just be peaceful. But none of our family are religious, so nothing like that came into it. But I always think – my grandma passed away quite a while ago so I always think, you know, they’ll be off having a glass of wine or a coffee or – you know, that’s the way I think. When someone goes they go and see the person that they [laughs] you know. So I sort of just –I just used to think that and then think of the happy times, you know, that I’d spent with my mum. So yeah. But it was never really a sad, sad thing.

Olivia: And I sometimes wonder if that’s why our hospital experience was so terrible, because actually we were grieving then.

David: Yeah. But no one could really understand it and we couldn’t because we didn’t have time.

Olivia: She was still there.

David: Yeah.

Cathy was shocked by the intensity of her grief at her brother’s funeral. She had been so focused on her brother that, after his death, she was left not knowing what to do.

Cathy was shocked by the intensity of her grief at her brother’s funeral. She had been so focused on her brother that, after his death, she was left not knowing what to do.

But he did a very good job, he was very kind. It was sunny. I don’t know the date of either Matthew’s death or funeral because I decided not to – I purposefully tried to avoid committing them to memory because I can’t escape from the date of his accident and from his birthday [cries] and I didn’t want to accumulate other days in which to feel just, you know, worse. But I didn’t know – I had thought I would feel relief at his funeral and I didn’t. I just was overwhelmed with this avalanche of grief, that I wasn’t expecting [cries] because I really did think I’d grieved. I really did think I’d grieved. And I didn’t think how – I think as well, I had felt – I felt I had a mission, you know.

So after Matty’s accident, I had a mission to make him better and then that didn’t work, but then we knew we had to do this, so that itself was a task I had to achieve for him, and then kind of when it was done, I just don’t think I knew what I was supposed to do with myself. And I think I’d thought – I’d expected that I would feel some kind of relief and I didn’t. I felt relieved for Matthew that he wasn’t alive anymore, for him. But I didn’t feel any – any relief for me at all.

When Morag’s father died, her mother – who had devoted nine years to caring for him - lost her whole ‘reason for being’.

When Morag’s father died, her mother – who had devoted nine years to caring for him - lost her whole ‘reason for being’.

Emma was pleased to be able to organise a lovely funeral for her mother, and then felt her own life could start again.

Emma was pleased to be able to organise a lovely funeral for her mother, and then felt her own life could start again.

Helen told us about the choice of gravestone for her son and the importance to being able to remember her son with happiness.

Helen told us about the choice of gravestone for her son and the importance to being able to remember her son with happiness.

Oh yes.

Can you tell me a bit about the choice of that – those, that wording?

Okay. For most people when they die on their epitaph you have when they were born and when they die. There’s no question, those are immovable. But for Christopher it was different. He was born on the seventh of September. He lost his life on the thirtieth of April. And he was finally at peace on the twenty-first of December. An awful lot of people don’t have that interregnum between the loss of life and being at peace. But he did. And it struck me important that they were each marked.

So there were many years between when he lost his life and when he was at peace?

Yes. But he is at peace now. Which makes it possible for us to take a deep breath and move on. And that perhaps is the biggest gift that he left for us. That we knew that he would want us to recover and remember him with happiness and remember the good times, and not to have our life overshadowed by on-going infections, hospital visits, problems with splints and everything else. But that we should actually get our own proper normal lives back to a degree.

“I fantasise about her funeral basically being able to be united and to celebrate her and you know remember her… we’re stuck. We’re all pressing against this glass wall. And when she dies... although it’s been so long, you kind of imagine it’s all going to be okay when she dies.”

Another said that she would not want anyone to wear black at her son’s funeral because: ‘it’s probably a celebration that he’s finally been released.’ And Ann and Bea discussed how they had wanted a little time to say good-bye to Fiona and plan her funeral in the week after her accident - plans which remain on hold as Fiona is still alive (in a vegetative state) many years later.

Bea: “I was really pleased that I’d had the chance to do that, she’d be really pleased with the decisions made for her funeral... planning a really nice do, and choosing the music was a decision of something that I could be proud of planning for her’.

Ann: ‘I was thinking, oh yeah, a month would be nice because, you know, we've had a chance to say goodbye to [Fiona], you know. And obviously, at that point, we didn't feel there was anything else we were going to be able to do for her.”

For those who had experienced a death, the funeral could be an important ritual celebrating the person as they would have wanted to be remembered.

Morag describes being part of a tightly-knit local community and the support at the funeral from the police force her father had been part of.

Morag describes being part of a tightly-knit local community and the support at the funeral from the police force her father had been part of.

Everyone remembered and knew him and –

And everyone had a story to tell about him. And he had a wicked sense of humour as well, a real wicked sense of humour, and everybody had a story about, you know, when they’d got drunk with him or when he’d played a trick on him or something or other. Apparently, I think that’s where I get my wickedness from.

David’s mother was given a great ‘send off’ at her funeral.

David’s mother was given a great ‘send off’ at her funeral.

Olivia: We bought her the smartest outfit from Per Una.

David: From – yeah, yeah, she looked really good. And then, yeah, she was taken to the crematorium, brief, non religious service, and then my dad up on guitar singing Irish Rover, Country Roads and Streets of London, [laughs] with a massive round of applause. And then she had her wake at the club that she used to work at. So that was quite fitting. And then back to the family home for I wouldn’t say a knees up but a drink, a laugh, a cry and yeah, a good sendoff I think, what she wanted. Well, one thing we knew she did want was a quick hearse to the crematorium. She said, “No creeping, just go at speed.” [Laughter] So we did, we did that. Yeah, and it was a good send off, wasn’t it?

Olivia: Yeah, it felt like her.

David: Fitting, very fitting.

Olivia: Yeah, a celebration.

David: My dad – to my dad – for my dad to sing rather than to make a speech or a, you know, a speech of her life. But basically the music told it all. If anyone knew mum and dad and singing, happiness was what she wanted.

Had you been planning the funeral for a while?

David: No, no, no. We only had less than a week. So we got everything prepared, flowers, etcetera, and then dad said he’d prefer to sing than speak. He probably couldn’t be able to get through it, so he sung. And there wasn’t a dry eye in the house, was there?

Olivia: No.

David: [Laughs] It was brilliant [Laughs].

Olivia: Everyone was joining in singing and clapping.

David: Everyone knew the songs, yeah. So—

Olivia: And the undertaker said he’d never been to a funeral quite like it.

David: [Laughs] so yeah, a good send off for sure.

Her son’s funeral was a lovely occasion, and Helen had the strong sense that her son was there with her.

Her son’s funeral was a lovely occasion, and Helen had the strong sense that her son was there with her.

And then we went to the nearest hotel and everybody took their wet shoes off… and we had obscene amounts of hot chocolate and toasted sandwiches and chocolate cake and we wished him well on his journey. And he was there with us, no question, he was there.

Last reviewed December 2017.

Copyright © 2024 University of Oxford. All rights reserved.